It’s amazing that in this day and age, the best way to search for new clothes is to click a few check boxes and then scroll through endless pictures. Why can’t you search for “green patterned scoop neck dress” and see one? Glisten is a new startup enabling just that by using computer vision to understand and list the most important aspects of the clothing in any photo.

Now, you may think this already exists. In a way, it does — but not a way that’s helpful. Co-founder Alice Deng encountered this while working on a fashion search project of her own while going to MIT.

“I was procrastinating by shopping online, and I searched for v-neck crop shirt, and only like 2 things came up. But when I scrolled through there were 20 or so,” she said. “I realized things were tagged in very inconsistent ways — and if the data is that gross when consumers see it, it’s probably even worse in the backend.”

As it turns out, computer vision systems have been trained to identify, really quite effectively, features of all kinds of images, from identifying dog breeds to recognizing facial expressions. When it comes to fashion, they do the same sort of thing: Look at the image and generate a list of features with corresponding confidence levels.

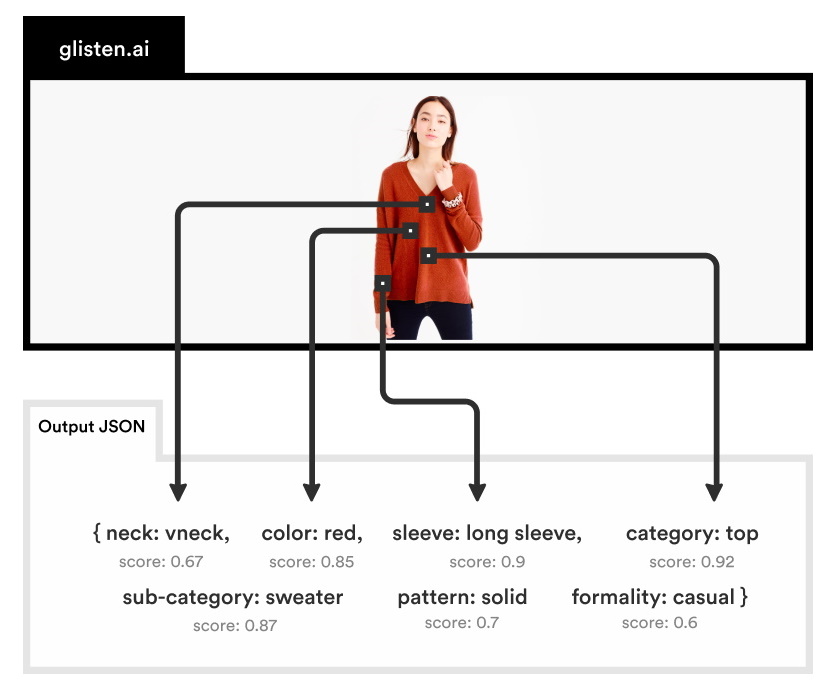

So for a given image, it would produce a sort of tag list, like this:

As you can imagine, that’s actually pretty useful. But it also leaves a lot to be desired. The system doesn’t really understand what “maroon” and “sleeve” really mean, except that they’re present in this image. If you asked the system what color the shirt is, it would be stumped unless you manually sorted through the list and said, these two things are colors, these are styles, these are variations of styles, and so on.

That’s not hard to do for one image, but a clothing retailer might have thousands of products, each with a dozen pictures, and new ones coming in weekly. Do you want to be the intern assigned to copying and pasting tags into sorted fields? No, and neither does anyone else. That’s the problem Glisten solves, by making the computer vision engine considerably more context-aware and its outputs much more useful.

Here’s the same image as it might be processed by Glisten’s system:

“Our API response will be actually, the neckline is this, the color is this, the pattern is this,” Deng said.

That kind of structured data can be plugged far more easily into a database and queried with confidence. Users (not necessarily consumers, as Deng explains later) can mix and match, knowing that when they say “long sleeves” the system has actually looked at the sleeves of the garment and determined that they are long.

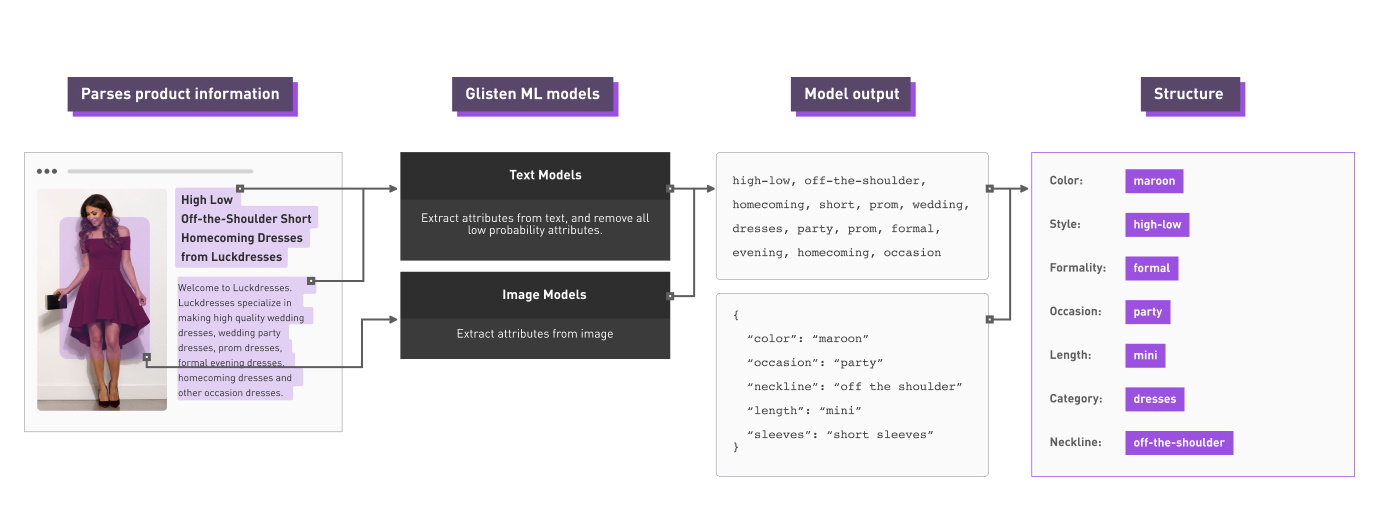

The system was trained on a growing library of around 11 million product images and corresponding descriptions, which the system parses using natural language processing to figure out what’s referring to what. That gives important contextual clues that prevent the model from thinking “formal” is a color or “cute” is an occasion. But you’d be right in thinking that it’s not quite as easy as just plugging in the data and letting the network figure it out.

Here’s a sort of idealized version of how it looks:

“There’s a lot of ambiguity in fashion terms and that’s definitely a problem,” Deng admitted, but far from an insurmountable one. “When we provide the output for our customers we sort of give each attribute a score. So if it’s ambiguous whether it’s a crew neck or a scoop neck, if the algorithm is working correctly it’ll put a lot of weight on both. If it’s not sure, it’ll give a lower confidence score. Our models are trained on the aggregate of how people labeled things, so you get an average of what people’s opinion is.”

Although shoppers will likely see the benefits of Glisten’s tech in time, the company has found that its customers are actually two steps removed from the point of sale.

“What we realized over time was that the right customer is the customer who feels the pain point of having messy unreliable product data,” Deng explained. “That’s mainly tech companies that work with retailers. Our first customer was actually a pricing optimization company, another was a digital marketing company. Those are pretty outside what we though the applications would be.”

It makes sense if you think about it. The more you know about the product, the more data you have to correlate with consumer behaviors, trends, and such. Knowing summer dresses are coming back, but knowing blue and green floral designs with 3/4 sleeves are coming back is better.

The model is initially aimed at fashion and clothing in general, but it can be adapted to other categories without having to reinvent the wheel — the same algorithms could find the defining characteristics of cars, beauty products, and so on.

Competition is mainly internal tagging teams (the manual review we established none of us would like to do) and general-purpose computer vision algorithms, which don’t produce the kind of structured data Glisten does.

Even ahead of Y Combinator’s demo day next week the company is already seeing 5 figures of monthly recurring revenue, with their sales process limited to individual outreach to people they thought would find it useful. “There’s been a crazy amount of sales these past few weeks,” Deng said.

Soon Glisten may be powering many a product search engine online, though ideally you won’t even notice — with luck you’ll just find what you’re looking for that much easier.