While attention continues to be focused on the rise and growing sophistication of voice-based interfaces, a startup that is using artificial intelligence to improve how we communicate through the written word has raised a round of funding to capitalise on its already profitable growth. Grammarly — which provides a toolkit used today by 20 million people to correct their written grammar, suggest better ways to write things and moderate the tone of what they are saying depending on who will be doing the reading — has closed a $90 million round of funding.

Brad Hoover, the company’s CEO, confirmed to TechCrunch that the funding catapults the company’s valuation to more than $1 billion as it gears up to grow to more users by expanding Grammarly’s tools and bringing them to more platforms. Today, Grammarly can be used across a number of browsers via browser extensions, as a web app, through mobile and on desktop apps, and through specific apps such as Microsoft Office. But the area where we communicate via the written word is expanding all the time — consider, for example, how much we use chat and texting apps for leisure and for work — so expect that list to continue growing.

“The mountain of digital communication is increasing, and in the workplace we have more distributed teams,” he said, “pointing to the importance of people presenting themselves in consistent and compelling ways.”

This latest round is being led by General Catalyst, which had also helped lead its previous and only other round, for $110 million in 2017, with participation from previous investor IVP and other, unnamed backers. It brings the total raised by the startup to $200 million.

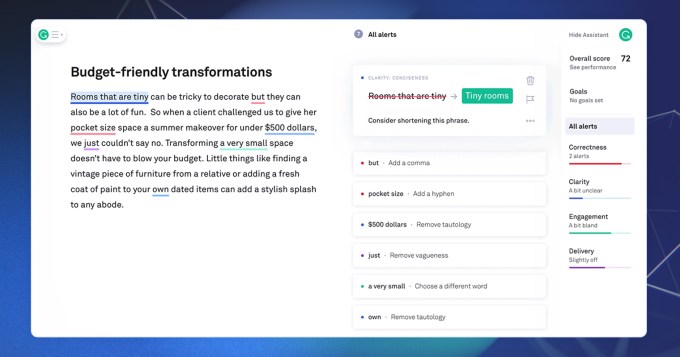

Grammarly today operates on a freemium model, where paid tiers give users more tools beyond grammar checks and conciseness to include things like “readability” detection, alternative vocabulary and tone suggestions (not to be confused with tone policing) and plagiarism checks, with tiers that are priced at $11.66, $19.98 and $29.95 per month. Hoover would not say how many of its users are taking paid tiers or how much the company makes from that, but he did confirm that, like others offering freemium, the majority of users are free ones.

(And like other free users, they are subject to cookies and the rest, but the company confirms to me that it doesn’t make any money from that, and only from its subscriptions revenues.

“We don’t sell or rent user data to third parties for any reason, including for them to deliver their ads. Period. Our business model is a freemium model, in which we offer a free version of our product as well as Grammarly Premium and Grammarly Business, which are paid upgrades,” a spokesperson said. “The only way Grammarly makes money is through its subscriptions.”

It notes that the lengthy privacy policy is going to be updated to make it shorter, but acknowledges the length can be off-putting.

“It is a fair critique to say that our privacy policy is longer and wordier than it needs to be. In an effort to comply with various disclosure requirements imposed by laws around the world, we have erred on the side of completeness and detail, sacrificing brevity in the process,” a spokesperson said. “Indeed, the sheer length of our privacy policy may be a barrier to users reading all the way through the document. The explicit statements we make about not selling or renting personal data and not sharing it for the purposes of advertising are contained toward the end.”

It’s worth noting that the company has been profitable almost from the start, when it was founded as a bootstrapped outfit in 2009 by Alex Shevchenko and Max Lytvyn, who continue to respectively work on product and revenue at the company (Hoover is the startup’s longtime CEO, having joined back in 2011).

Its singularity of focus and simple message — it’s only available in English and only for written communications, with no plans to expand currently into other languages or other mediums like audio — has partly been the reason why Grammarly has found interesting traction in the market, but it’s also a consequence of the endeavor itself. The company brings together not just a vast trove of data about proper grammar, but using AI techniques around machine learning and natural language processing it is constantly synthesizing new words and phrases and styles to improve the help that it provides to users, to solve what is essentially an everyday problem for many people: writing well.

“Grammarly is solving real challenges that people face every time they pick up a device to answer a text, answer a work email or cold email a potential client,” said Hemant Taneja, who led the investment for General Catalyst, in an interview.

“While there are large companies attempting to innovate in this space, creating intuitive AI that complements our natural communication abilities isn’t their primary focus. It’s not even their third, fourth or twentieth focus. For Grammarly, helping people communicate more effectively is their sole goal. And that’s why, despite any competition, they’ve got more than 20 million daily active users.” That 20 million figure is more than three times the number of users Grammarly had in 2017.

Nevertheless, a number of would-be competitors have emerged to provide similar tools or those that directly compete with slightly different propositions. Google, for example, today gives you prompts of what to say when responding to an email, in the form of stock sentences or cues while you are writing. Hoover says these are less of a worry to Grammarly for a couple of reasons. The first is its approach to be available around whatever you might be writing, and the second is it’s platform-agnostic state, which means it’s potentially wherever you are writing, too.

“We haven’t seen any impact from the rise of platform-based aids,” Hoover said.

Looking ahead, he added that while Grammarly will be making its way to more platforms, the company will be creating more tools specifically to better court enterprise customers and the use cases that are more specific to them.

While that will not (yet) extend to verbal communication or other languages beyond English, there will be more tools built on the concept of “style guides” for people in specific departments, such as customer service, to remain consistent in their language and how they speak for the company to the outside world.

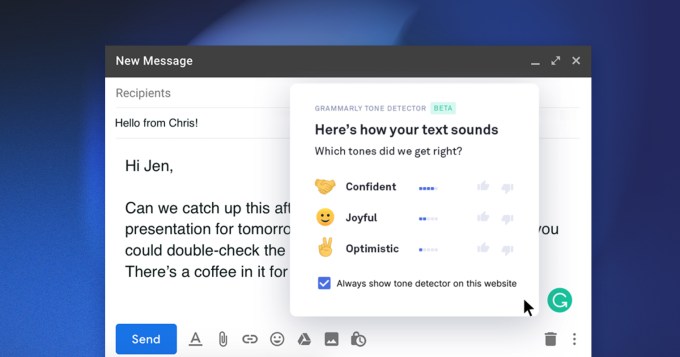

“One of the reasons enterprises use Grammarly is to increase effectiveness both internally and externally,” Hoover said. “This isn’t a tool to write on behalf of users but to be used as a coach.” This is also where the tone tool fits into the spectrum, he added.

“We surveyed our users and the results suggested that a majority were concerned about the appropriate tone that they used in written communication,” he said. “That’s not surprising because unlike spoken or in-person communications, you can’t use non-verbal tones to get an idea across, so you can be misinterpreted.”