Depending on which study you believe, the wearable and digital health market could be worth anywhere from $30 billion to nearly $90 billion in the next six years.

If the numbers around the size of the market are a moving target, just think about how to gauge the validity and efficacy of the products that are behind all of those billions of dollars in spending.

Andy Coravos, the co-founder of Elektra Labs, certainly has.

Coravos, whose parents were a dentist and a nurse practitioner, has been thinking about healthcare for a long time. After a stint in private equity and consulting, she took a coding bootcamp and returned to the world she was raised in by taking an internship with the digital therapeutics company Akili Interactive.

Coravos always thought she wanted to be in healthcare, but there was one thing holding her back, she says. “I’m really bad with blood.”

That’s why digital therapeutics made sense. The stint at Akili led to a position at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as an entrepreneur in residence, which led to the creation of Elektra Labs roughly two years ago.

Now the company is launching Atlas, which aims to catalog the biometric monitoring technologies that are flooding the consumer health market.

These monitoring technologies, and the applications layered on top of them, have profound implications for consumer health, but there’s been no single place to gauge how effective they are, or whether the suggestions they’re making about how their tools can be used are even valid. Atlas and Elektra are out to change that.

The FDA has been accelerating its clearances for software-driven products like the atrial fibrillation detection algorithm on the Apple Watch and the ActiGraph activity monitors. And big pharma companies like Roche, Pfizer and Novartis have been investing in these technologies to collect digital biomarker data and improve clinical trials.

Connected technologies could provide better care, but the technologies aren’t without risks. Specifically, the accuracy of data and the potential for bias inherent in algorithms that were created using flawed data sets mean there’s a lot of oversight that still needs to be done, and consumers and pharmaceutical companies need to have a source of easily accessible data about the industry.

”The increase in FDA clearances for digital health products coupled with heavy investment in technology has led to accelerated adoption of connected tools in both clinical trials and routine care. However, this adoption has not come without controversy,” said Coravos in a statement. “During my time as an Entrepreneur in Residence in the FDA’s Digital Health Unit, it became clear to me that like pharmacies which review, prepare, and dispense drug components, our healthcare system needs infrastructure to review, prepare, and dispense connected technologies components.”

The analogy to a pharmacy isn’t an exact fit, because Elektra Labs currently doesn’t prepare or dispense any of the treatments that it reviews. But Atlas is clearly the first pillar that the digital therapeutics industry needs as it looks to supplant pharmaceuticals as treatments for some of the largest and most expensive chronic conditions (like diabetes).

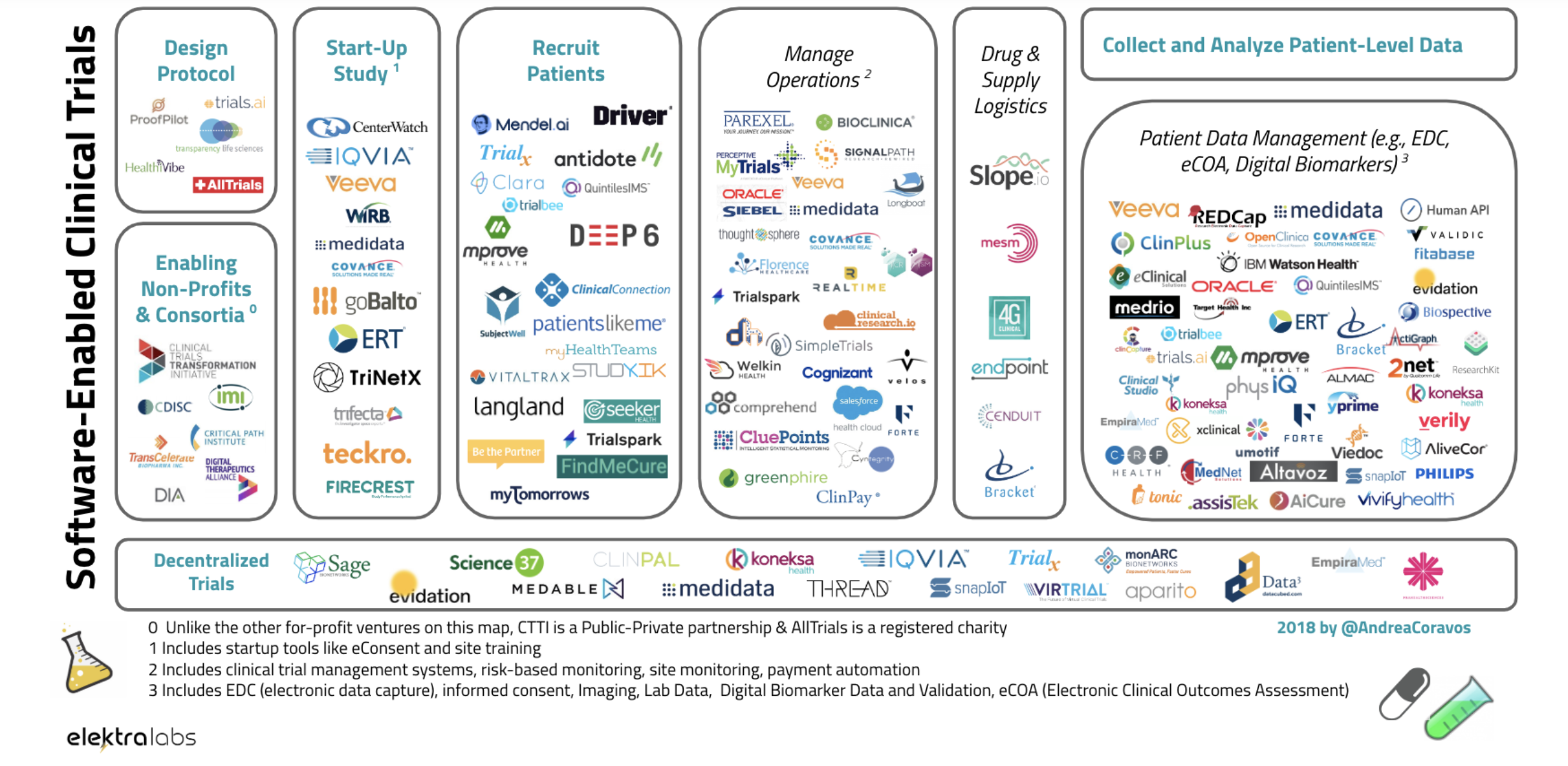

Courtesy of Andrea Coravos/Elektra Labs

Coravos and here team interviewed more than 300 professionals as they built the Atlas toolkit for pharmaceutical companies and other healthcare stakeholders seeking a one-stop shop for all their digital healthcare data needs. Like a drug label, or nutrition label, Atlas publishes labels that highlight issues around the usability, validation, utility, security and data governance of a product.

In an article in Quartz earlier this year, Coravos made her pitch for Elektra Labs and the types of things it would monitor for the nascent digital therapeutics industry. It includes the ability to handle adverse events involving digital therapies by providing a single source where problems could be reported; a basic description for consumers of how the products work; an assessment of who should actually receive digital therapies, based on the assessment of how well certain digital products perform with certain users; a description of a digital therapy’s provenance and how it was developed; a database of the potential risks associated with the product; and a record of the product’s security and privacy features.

As the projections on market size show, the problem isn’t going to get any smaller. As Google’s recent acquisition bid for Fitbit and the company’s reported partnership with Ascension on “Project Nightingale” to collect and digitize more patient data shows, the intersection of technology and healthcare is a huge opportunity for technology companies.

“Google is investing more. Apple is investing more… More and more of these devices are getting FDA cleared and they’re becoming not just wellness tools but healthcare tools,” says Coravos of the explosion of digital devices pitching potential health and wellness benefits.

Elektra Labs is already working with undisclosed pharmaceutical companies to map out the digital therapeutic environment and identify companies that might be appropriate partners for clinical trials or acquisition targets in the digital market.

“The FDA is thinking about these digital technologies, but there were a lot of gaps,” says Coravos. And those gaps are what Elektra Labs is designed to fill.

At its core, the company is developing a catalog of the digital biomarkers that modern sensing technologies can track and how effective different products are at providing those measurements. The company is also on the lookout for peer-reviewed published research or any clinical trial data about how effective various digital products are.

Backing Coravos and her vision for the digital pharmacy of the future are venture capital investors, including Maverick Ventures, Arkitekt Ventures, Boost VC, Founder Collective, Lux Capital, SV Angel and Village Global.

Alongside several angel investors, including the founders and chief executives from companies including: PillPack, Flatiron Health, National Vision, Shippo, Revel and Verge Genomics, the venture investors pitched in for a total of $2.9 million in seed funding for Coravos’ latest venture.

“Timing seems right for what Elektra is building,” wrote Brandon Reeves, an investor at Lux Capital, which was one of the first institutional investors in the company. “We have seen the zeitgeist around privacy data in applications on mobile phones and now starting to have the convo in the public domain about our most sensitive data (health).”

If the validation of efficacy is one key tenet of the Atlas platform, then security is the other big emphasis of the company’s digital therapeutic assessment. Indeed, Coravos believes that the two go hand-in-hand. As privacy issues proliferate across the internet, Coravos believes that the same troubles are exponentially compounded by internet-connected devices that are monitoring the most sensitive information that a person has — their own health records.

In an article for Wired, Koravos wrote:

Our healthcare system has strong protections for patients’ biospecimens, like blood or genomic data, but what about our digital specimens? Due to an increase in biometric surveillance from digital tools—which can recognize our face, gait, speech, and behavioral patterns—data rights and governance become critical. Terms of service that gain user consent one time, upon sign-up, are no longer sufficient. We need better social contracts that have informed consent baked into the products themselves and can be adjusted as user preferences change over time.

We need to ensure that the industry has strong ethical underpinning as it brings these monitoring and surveillance tools into the mainstream. Inspired by the Hippocratic Oath—a symbolic promise to provide care in the best interest of patients—a number of security researchers have drafted a new version for Connected Medical Devices.

With more effective regulations, increased commercial activity, and strong governance, software-driven medical products are poised to change healthcare delivery. At this rate, apps and algorithms have the opportunity to augment doctors and complement—or even replace—drugs sooner than we think.