The houses along the tree-lined blocks of Josina Avenue in Palo Alto, with their big back yards, swimming pools and driveways are about as far removed from the snarls of traffic, sputtering diesel engines, and smoggy air of South America’s major metropolises as one can get.

But it was in one of those houses, about a twelve-minute bicycle ride from Stanford University, that the seed was planted for what has become a renaissance in technology entrepreneurship in Latin America.

Back in 2010, when Adeyemi Ajao, Carlo Dapuzzo, and Juan de Antonio were students at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business they could not predict that they would be counted among the vanguard of investors and entrepreneurs transforming Latin America’s startup economy.

At the time, Ajao was negotiating the sale of his first business, the Spanish social networking company, Tuenti, to Telefonica (in what would be a $100 million exit). Carlo Dapuzzo was in Palo Alto taking a break from his job at Monashees, which at that time was a small, early-stage investment fund based in Brazil focused on investing in Latin America. Juan de Antonio had left a job as a consultant at BCG to attend Stanford’s business school on a Fulbright scholarship.

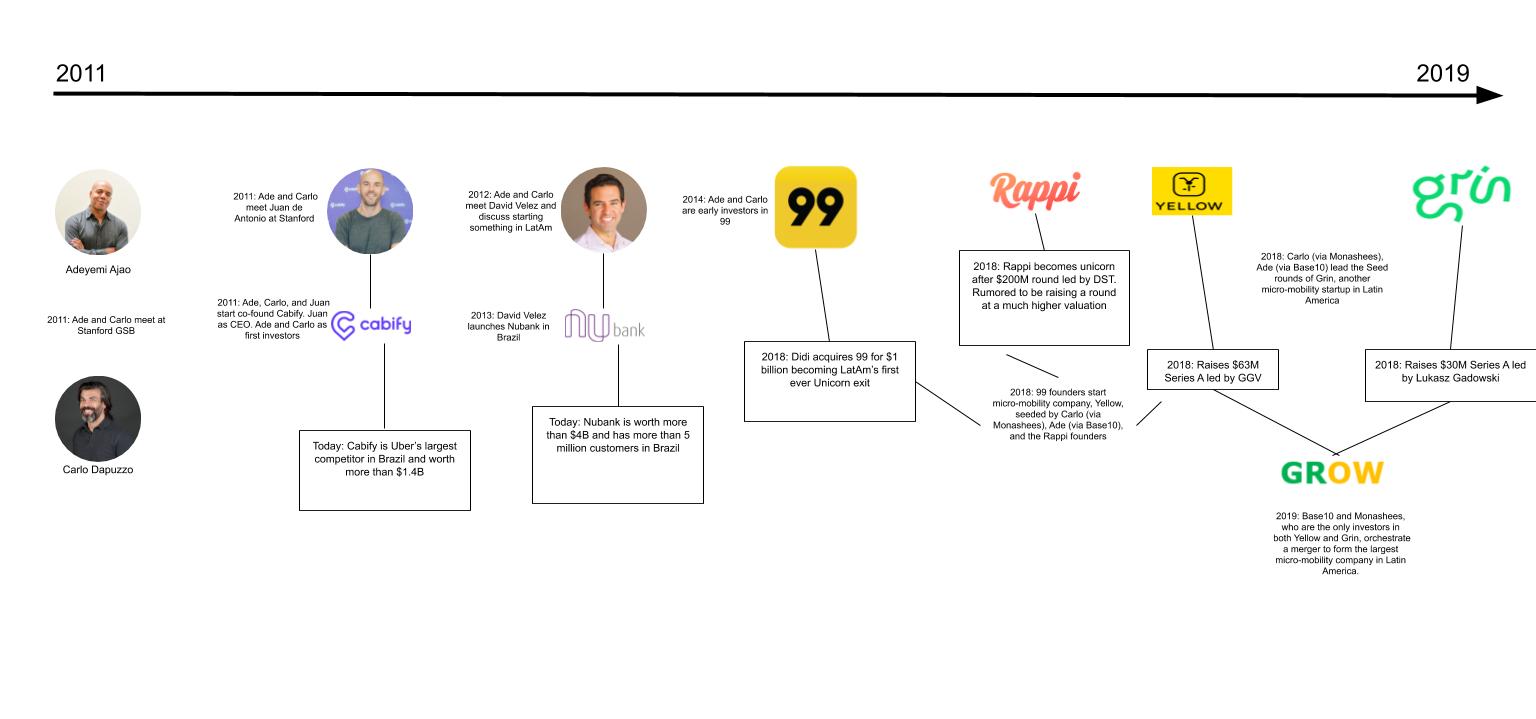

In just two years, Ajao would be a founding investor in de Antonio’s ride-hailing business, Cabify, focused on Latin America and Europe; and Dapuzzo would be seeding the ride-hailing service 99Taxis. Today, Cabify is worth over $1 billion and has focused its business primarily on Latin America while 99 was sold to the Chinese ride-hailing company Didi for $1 billion — making it one of the largest deals in Latin America’s young startup history.

The three men are now at the center of a vast web of startups whose intersection can, in many cases, be traced back to the house on Josina Avenue where Dapuzzo and de Antonio lived and where Ajao spent much of his free time.

“It’s the same dynamics as the PayPal Mafia,” says Ajao. “The new unicorn batches which started in Colombia, Mexico, and Brazil. Although they’re all trans-national, they all know each other and literally they are all friends and all co-investors in each other’s companies and they all have links to Silicon Valley… and… more importantly… to Stanford.”

Carlo Dapuzzo, Adeyemi Ajao, and Juan de Antonio at Stanford University

Stalled economic engines

If Ajao’s enthusiasm sounds familiar, that’s because it is. There was another wave of interest in Latin America that started surging nearly a decade ago, but crashed nearly five years into what was supposed to be the time of the region’s explosive growth in the global scene.

Back in 2008, as the U.S. was sliding into recession, global economists cast about for countries whose economic might could potentially provide some antidote to the toxic assets that were poisoning the global financial system in America and Western Europe. It was then that the concept coined by a Goldman Sachs economist back in 2001 (in the aftermath of another financial shock) baked Brazil, Russia, India and China into a BRIC — a group of nations that, as a bloc, could create enough growth to keep the global economy moving upwards.

All of them were growing at a rapid clip, albeit at different speeds and from different starting trajectories. But they were still all humming. Investment — from large financial institutions, private equity and venture capital firms — all began flowing into the four countries.

In Brazil and across Latin America, companies from the U.S. began to cast their eyes South for growth. That’s when Groupon began to make inroads into the region. When Groupon acquired the Chilean company ClanDescuento, it served as a starting gun for activity across multiple geographies.

Two years after that acquisition by Groupon, Redpoint’s Brazilian investment vehicle, Redpoint eVentures was able to close on a $130 million fund for Brazilian and Latin American investments in just under four months. While Brazil held the bulk of the capital, many of the largest startup companies were being launched out of Buenos Aires in Argentina.

Globant, Despegar, MercadoLibre, and OLX were all lucrative deals for the investors who made them. Today, they remain solid companies, but they didn’t create the ecosystem that both local investors and entrepreneurs were hoping for. Brazil’s Peixe Urbano was also a rising star at the time, but it too wound up selling, in its case to Chinese internet Baidu. Indeed, the Peixe Urbano funding gave investors like Benchmark’s Matt Cohler their first exposure to the region.

A 2012 default on Argentinian debt derailed the economy and Brazil’s economy began seizing up at around the same time. Then, in 2014, Brazil was hit by both an economic and political collapse that shook the country’s stability and ushered in a two-year-long recession.

Ultimately, the Brazilian component of the BRIC miracle, that would have potentially ushered in a brighter future for the broader region, didn’t materialize.

The next starting gun

Ajao began investing in Latin America as an angel investor during the beginnings of the downturn in Brazil and when Argentina was also seizing up. It’s also when Dapuzzo made the initial bet on 99Taxis — bringing Ajao in as an investor — and Cabify launched, eventually bringing its service to Mexico and seeing huge growth in the Latin American market.

500 Startups expanded to Mexico around the same period, in what turned out to be a prescient move. Because even as the broader economies were slowing, technology adoption — fueled by rising smartphone sales and new internet-enabled mobile services — was speeding up.

Groupon’s push into the region taught a new consumer market about the pleasures of venture-backed e-commerce, but it was ride-hailing that truly paved the way for Latin America’s future success. Many factors played a role, from the rise of smartphones to the stabilization and growth of economies in the region outside of Argentina and Brazil and the return of a generation of founders who gained exposure and experience in Silicon Valley.

Here again, the house on Josina Street and the friends that were made over the course of the two-year grad school program at Stanford would play a critical role.

“99 was the second start and this new generation of founders,” said one investor with a deep knowledge of the region.

A taxi driver uses the 99 taxi app for smartphones in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on October 11, 2018. (Photo via Nelson Almeida/AFP/Getty Images)

A herd of unicorns

Ajao also sees 99 as ground zero for the network that has spawned a unicorn stampede in Latin America. It’s a group of companies that covers everything from financial services, mobility and logistics, food delivery and even pet care.

In some ways it’s an extension and culmination of the American on-demand thesis, with allowances for the unique characteristics of the region’s varied economies and cultural experience, investors and entrepreneurs said.

“In my mind 99 had a lot to do with what is happening right now with the current PayPal mafia [of Latin America] because they became the first big new exit on the continent,” Ajao says.

Entrepreneurs from 99 spun out to form Yellow, a dockless scooter and bike-sharing company that was initially backed by Monashees, Grishin Robotics and Base10 Partners — the venture firm that Ajao co-founded and which closed a $137 million venture fund just nine months ago.

Monashees and Base10 also co-invested in Grin, a Mexico City-based dockless scooter company. Together the two companies managed to raise over $100 million before merging into one company earlier this. That deal ultimately provided a challenger to the automotive-based ride-sharing businesses that were beginning to encroach on the scooter business.

The growth of 99Taxis and the rise of startups in Latin America ultimately convinced David Velez, a former venture investor with Sequoia Capital to return to Brazil and try his hand at entrepreneurship as well. A year behind Ajao, de Antonio and Dapuzzo at Stanford, Velez was also friendly with the group.

Velez worked at Sequoia Capital and saw the opportunity that Latin America presented as an investment environment. After starting Sequoia Capital Latin America he transitioned into an entrepreneurial role and became the co-founder of Nubank, which would be Sequoia’s first Latin America investment. Now a $4 billion financial technology powerhouse, the Nubank deal was yet another proof point that the Latin American market had come of age — and another branch on a tree that has its roots in Stanford’s business school and the Silicon Valley venture community.

The final piece of this intersecting web of investments and relationships is Rappi — the Colombian delivery service business that was also backed by Monazhees and Base10. The first company from Latin America to enter YCombinator and the first investment from the new Silicon Valley power player, Andreessen Horowitz, Rappi epitomizes the new generation of Latin American startups.

“The way we think about this part of the world is as a massive market with 700 million people living on the continent and really dense cities,” says Rappi co-founder and president, Sebastian Mejia. “And it’s a region where the tech stack hasn’t been built, which gives you an opportunity to solve problems and create digital champions that look more similar to China than the U.S.”

Mejia epitomizes what Ajao calls a new breed of startup entrepreneur that doesn’t necessarily look to other markets for inspiration or business models, but solves local problems for a local customer, rather than a global one.

“Being local was more of a competitive advantage than a disadvantage and we can solve problems in a better way than a Silicon Valley company or a Chinese company could,” says Mejia. “What we’re starting to see now is that those changes in perspective allow us to build bigger companies.”

In all, Monashees and Base10 have invested in companies operating in Latin America that have a combined valuation of over $6 billion between them. Through the extended network of Stanford connections and the startups that Velez has brought to the table that number is higher than $10 billion.

A bicycle courier working for Colombian online delivery company “Rappi”, rides his bike in Bogota, on October 11, 2018. (Photo via John Vizcaino/AFP/Getty Images)

The next $10 billion

If the Latin American market was once overlooked by venture investors like Sequoia Capital, Andreessen Horowitz, Benchmark or Accel, that’s certainly no longer the case.

Funds are pouring into the region at an unprecedented clip, driven by SoftBank and its interest on the continent following its commitment to launching a new $2 billion fund in the region and its subsequent $1 billion investment in Rappi.

“Latin America is on the cusp of becoming one of the most important economic regions in the world, and we anticipate significant growth in the decades ahead,” said Masayoshi Son, chairman and CEO of SBG, in a statement when SoftBank launched its fund.

“SBG plans to invest in entrepreneurs throughout Latin America and use technology to help address the challenges faced by many emerging economies with the goal of improving the lives of millions of Latin Americans,” he added.

Son is likely thinking about the 375 million internet users in Latin America and the 250 million smartphone users across the region. It’s also worth noting that retail e-commerce has been a huge driver of economic growth despite other economic obstacles. The region’s e-commerce has grown to $54 billion in 2018 up from $29.8 billion in 2015.

Even more critically, there are some key areas where innovation and new services are still sorely needed. Access to transportation isn’t great for the roughly 79% of the 700 million people across South America who live in cities. Then there are 400 million people across Latin America who are either unbanked or underbanked. Healthcare is another area where a lack of investment to date could create potential opportunities for new startups.

More generally, poor infrastructure remains a significant problem that companies like Rappi and another SoftBank investment, Loggi, are looking to make inroads into.

“Latin America was for many years, underinvested,” says de Antonio, whose Cabify business has managed to score a valuation of over $1 billion largely based on the opportunities ahead of it in the Latin American market. “You will see a bit more money to catch up. The market is big… and potentially huge… I’m a big believer that it’s a good moment now to invest.”

For de Antonio, Cabify, Rappi, and other startups are only now hitting their stride. In the future, they stand to enable a host of other opportunities, he believes.

“The entrepreneurial mindset is really ingrained in Latin America… the difference is maybe there wasn’t an ecosystem to help these ideas to scale.. .there are huge fortunes in the region but they typically… they have a lot of their assets invested in the region… but they need to diversify,” said de Antonio. “Until recently there hasn’t been an active funding market for all of these startups.”

For de Antonio and Ajao, one of the critical lessons that they learned from their time at Stanford and being exposed to the broader Silicon Valley ecosystem was the notion of collaboration.

“This is something we learned from San Francisco,” de Antonio said. “The way companies help each other is something that we haven’t seen people do before. And usually when you are a young company this can be the difference between being successful or a failure.