One problem is the national exam is focussed on reading and writing english, so many people in China do not get a chance to practice conversations

The next time you hear a native Chinese speaker call themselves a ‘homeboy’ in English, don’t assume that they’re trying to be cool.

“Homeboy is Chinglish for zhainan,” explains Zoe Zhou, the COO of Seed, a language education startup based in Shanghai. In Chinese, zhainan, which literally translates to ‘home man’, refers to males who don’t leave the house and avoid social contact – quite different from the comparable English expression.

“One of the biggest challenges [for our users] is speaking English,” she says. “It’s hard to practice at school, […] and they don’t know if what they’re saying is right or wrong.”

National exams in China, such as the gaokao college-entrance exam, test students on their English language abilities, but most of the emphasis is placed on reading and writing, not speaking. For example, an exam might require students to recognize hundreds of English vocabulary words, but not test them on their ability to carry on a conversation.

For students who want to study abroad or professionals who work in foreign companies, oral English proficiency is a must. In China, a multitude of companies have risen to cater to this demand, such as 51Talk, which offers one-on-one phone calls with Filipino teachers, as well as apps like Liulishuo (流利说) and Youdao ‘Spoken English Master’ (有道口语大师, our translation).

Also Read: These three players dominate China’s consolidated food delivery market

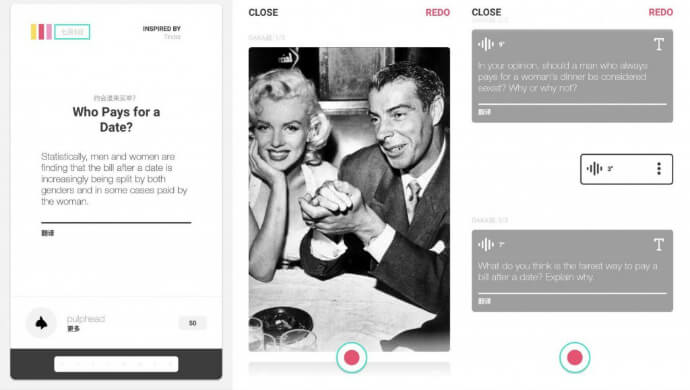

Daka (打卡), Seed’s latest app, isn’t about fixing pronunciation, nor does it offer users a set of lessons or training material. The app gives users one exercise per day, consisting of three questions. Each exercise is centered around a provocative prompt or topic. The point is to get users talking about topics that they normally discuss with their friends, says Ms. Zhou.

“Young Chinese people have their own unique perspective on a lot of topics,” says Ms. Zhou. “We hope that by helping them practice [speaking English], we can help them express themselves.”

“[Self-expression] is missing in a lot of traditional Chinese education and training,” she says. “A lot of exams are about facts, like what date is National Day? But they won’t ask […] what are your thoughts? Do you think they did the right thing or the wrong thing?”

In addition to inciting users to talk, Daka’s prompts are also designed to push users to think critically and defend their own opinions. For example, an exercise might start off by asking users what they think about the Yulin Dog Meat Festival, says Ms. Zhou. The next question will then follow up on the first one, and ask users how eating dogs is different from eating fish, which is a widely accepted practice despite the fact that fish can also be pets.

Daka, which launched a few weeks ago, is meant to be paired with Seed’s previous app, which curates English content for users. The company hopes that users will be able to pick up new words and phrases from their first app and apply them in Daka, which means “to clock in” in Chinese.

Daka will have to battle the user attrition typically associated with smartphone app usage, especially as a language learning app that wants its users to practice regularly. According to a study by analytics firm Localytics, 23% of users abandon an app after just one use. Seed is hoping to encourage its users to “clock in” everyday with a credit system, where users are rewarded for starting the daily exercise, as well as completing it. In the future, these credits can be redeemed for teacher feedback on audio responses.

Also Read: This ex-Uber exec is creating China’s Uber for bicycles

Human teachers are typically one of the biggest costs in any language learning company, and it’s not clear whether or not Daka’s credit system will be enough to cover those expenses. However, the company is focusing on growing their user base at the moment, not generating profit, says Ms. Zhou.

—

The article This Education Startup Wants To Help Chinese People Avoid Chinglish first appeared on Technode.

Photo courtesy of Seed.

The post This education startup wants to help Chinese people avoid Chinglish appeared first on e27.