Here’s the story of how a tech-savvy lady overcame obstacles to make her mark in Japan’s nascent tech startup industry

The year is 2008. Within the vaunted halls of the financial industry, trouble is brewing. It is the beginnings of the subprime mortgage crisis — a major financial crisis whose ripples is still felt today. Investment banking giant Lehman Brothers becomes the first domino to fall; Then, Goldman Sachs takes a massive beating.

Somewhere in Tokyo, Japan, a young 24 year-old Goldman Sachs executive named Akiko Naka witnesses the fallout up close. She’s barely out of university — bright-eyed and eager to make her stamp on the world. This development does not bode well with her.

The scene is not pretty. The herd is being thinned out. Just a year into her job, she is watching some of her colleagues pack up and leave, never to return. To make matters worse, who gets the chop is a decision based on internal politics, as opposed to skills competency.

While Naka is spared the guillotine, the outlook remains sombre. It is one ghastly wreck of a situation, and it has left a bitter taste in her mouth.

“I was fed up with the situation and I wasn’t really interested in the financial space in the first place,” recounts Naka, in an interview with e27.

Nevertheless, her stint at the global investment bank taught her many invaluable lessons and skills.

“People in Goldman Sachs are really talented. It was good to learn from their high standards of work and ethics, because the first work ethic you learn will determine how you behave for the rest of your career,” she says.

“And they treated women and men equally. Women worked as hard as men. They might have kids but after two or three weeks, they outsource all the household stuff to their nannies,” she says.

But the stuffy, suit-and-tie, corporate executive lifestyle was ill-suited for her. For Naka, she derives more gratification from a screen of code than from a page of financial statements. Technology was always going to be her first love.

The beginnings of a life-long passion

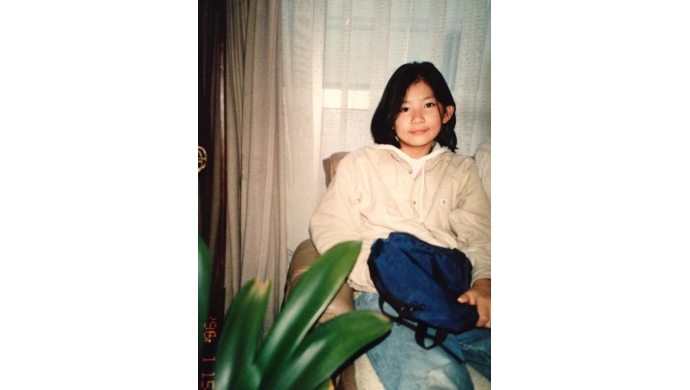

Born to parents who work in academia — a father who taught computer science in universities, Naka was exposed to computers at a very early age.

“In 1996, when I was about 12/13 years old, I built my first website, which is quite early because the internet was not common then. Kids nowadays have the internet, but I’m like the generation between the digital native and people who are not-so-internet-savvy,” she says.

And computers back then were considered very nerdy. She even had to hide her “secret hobby” from her friends, Naka recounts with a laugh.

One of her motivations to pursue tech was also motivated by money. As a child of two professors, their combined income did not afford her much financial freedom (as much as she would have liked, anyway).

“Academic people don’t get paid very well when they are young. So I had to restrain myself from spending money. I wanted the freedom to do whatever I want with my money. So I was interested in business,” she says.

While studying for an Economics degree at the Kyoto University, Naka, armed with basic HTML coding skills, took on some freelance gigs building websites for clients. She also interned at a small media company run by a university graduate three years her senior. That was her first taste of managing a business.

“I thought I was smarter than everybody, and I kind of looked down on them [colleagues] because I thought I could handle things better than them,” she recalls with a laugh.

At the company, she kickstarted publishing a magazine that was distributed for free on campus. One of her major accomplishments was clinching a deal with a major record label to feature a major artist on the cover page. Not bad, she says, for 22 year-old college student.

Also Read: 3 tips for entering the Japanese startup ecosystem from a local investor

Then she met a friend. And together with a team of four people, they sought to build a social network. It was a time when Friendster and MySpace were still leading the social media pack — and Facebook had just moved out of the college dorm.

“In Japan, there were new social networks coming out, like Mixi. But it was like kid’s play — not serious at all,” she recalls. (Mixi has since gone into decline).

But after a while, the project fizzled out.

“People [her team] got tired of work that was going nowhere. The project was not scalable and there was no meaning or purpose to it. After that, I was kind of sick of running a business and thought of getting a proper job,” she says.

Taking the path most treaded

Back in the mid-2000s, the tech industry in Japan, according to Naka, was “shady” and unappealing. It lacked the rock n’ roll appeal of Silicon Valley, where founders were revered, and whose caricatures and backroom drama became the stuff of award-winning Hollywood pictures.

“Back then, people [in Japan] thought that the internet industry was dark and shady; You had to work long hours and you didn’t get rewarded much,” she says.

“In Japan, your education level decides everything — whether you go to a good university, whether you get a good job and enjoy your life. But if you are going to screw up your entry level exam and go to a bad school, you are going to have a tough, tough time getting a really good job,” she says.

Going out there to build your tech company was perceived a second chance to succeed.

“It was a high risk, high return venture — but in a shady space,” she says.

So it was off to the university’s job fair — a rite of passage for every final year Japanese university student — for Naka. She applied for Goldman Sachs, ready to embark on a lifelong career.

Less than two years later, she found herself once again at a fork in the road.

But it was technology she returned to (at least, not immediately), her aspirations took a more unusual turn. Naka is a woman of many talents, and one of that was drawing.

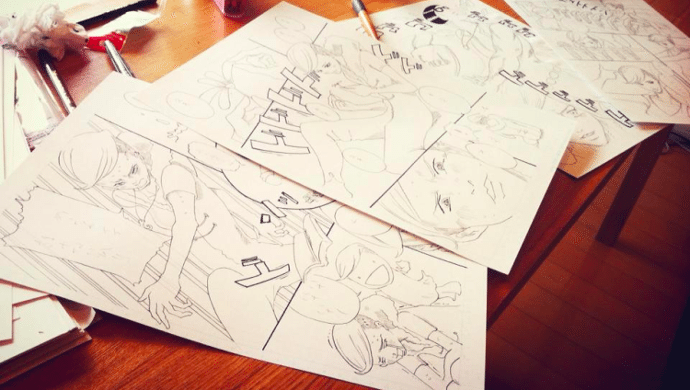

“It sounds crazy but I always had this dream of becoming a manga (Japanese comics) artist. I was really good at drawing. In Japan, one of the few passions you can pursue if you are good at drawing is becoming a manga artist,” she says.

“It’s a profession you can really look up to. Japanese people think being a manga artist is a prestigious job. And if you succeed, you can really make tons of money,” she adds.

Naka spent a year focussing on working on her own science fiction manga comics, where she says she has just published on Amazon Kindle recently.

“Whenever I tell this story to the Japanese media, they don’t take me seriously,” she says, with a laugh.

“I think I’m really good at starting things from scratch, creating from zero.”

Technology comes back into play

They say you never really get over your first love. For Naka, it was not long before her passion for tinkering with tech came creeping back in. And she found a way to merge it with her manga enterprise.

“I had this idea of creating a website where people can publish or upload a manga and have other people translate it. The problem for Japanese manga artists is that there is only a limited market inside Japan,” says Naka.

She set to work finding a team through freelancer platform Elance (now known as Upwork). Over there, she managed to hire Israeli programmers and together they worked on building a Japanese manga translation website called Magajin (TechCrunch describes it as a “deviantART for manga with social translation built in”). The translations are either community-sourced or done via a rudimentary algorithm.

Also Read: 5 of the best apps to help English speakers translate and learn Japanese on Android

“It didn’t work very well. It was supposed to be able to allow users to input translated texts into the speech bubbles of the characters but that didn’t work out. Eventually, all we did was upload illustrations and stuff and people would comment and then users would translate that comment,” she says.

There were many functionalities on the platform, including a built-in dictionary where users could add words. Eventually, the website grew to about 10,000 users. But it would not float for long.

“At some point, it had to make money, but the only audience I had were kids. I had so many [users] in Europe and the US but they were all 12 to 15 year old kids with no money. Yeah, I figured it was not sustainable,” she says.

But from the doomed project came a silver lining — a connection to Facebook. While in process of growing Magajin, she joined a tech conference in Tokyo to promote the site. Over there, she met with Facebook Japan’s executives, who subsequently offered her a job.

Her Facebook Japan gig in 2010 would eventually become the primer for her own company Wantedly. The free-spirited and innovation-driven working culture of Facebook became a major influence on Naka. It was also where she got her first proper crash course in platform design.

“I knew how to build websites and market them but these were all self-taught. I didn’t learn the proper techniques, cool theories, structures and framework until I was there [in Facebook Japan]. So I was like ‘Wow! This is cool!’,” says Naka.

“For example, I didn’t even know the term user interface and user experience and design until I joined Facebook. I learnt that when building websites, you need to make it easy for the users; You need to cut off excess functions and stuff,” she adds.

Then, there was the organisational structure, which stood far apart from the investment banking culture.

“I was beginning to get influenced by Facebook’s culture. At Goldman Sachs, the sales people ran and dictated everything. But at Facebook, the engineers were at the centre of the organisation,” says Naka.

Also Read: Japan’s startup scene: Centures-old craft and new tech

“Marketers and sales — they follow the instructions of the engineers. The engineers would build and ship, so there was little room for negotiation and discussion. It was about moving fast, and failure was a cool thing. If they shipped [a feature] and it didn’t work, they would just drop it,” she says.

Naka attributes Facebook’s open and fluid culture to the young age of the employees — People who were hungry to experiment and push the boundaries.

But after six months at Facebook Japan, Naka was once again getting restless.

“I was kind of agitated because I was turning 25 back then and I wanted to do something. I wanted to be somebody while I was in my 20s,” she says.

She started work on the first prototype of Wantedly, a job search site that was based on Facebook’s sociographics and platform. It would be like how TripAdvisor integrates Facebook into its platform, she says.

Her vision of Wantedly was something that would be “influential, beautiful, and smart.”

“I really look up to Steve Jobs, even though he is a really horrible person,” says Naka with a laugh.

“The products he built are so influential and changed a lot of people’s lives. Some companies are really successful but the products they built are not really clean or simple. Some people just use their products because it’s cheap or something. But Apple’s products brought people’s lifestyle to the next higher level — with their clean, beautiful design and interface,” she says.

But at that point in time, she had trouble finding a competent programmer. Eventually, after some networking, she found an engineer who would work with her. The only problem was that he had a day job.

“He would code after work, then would start coding for me from like 10pm to 2am for me. This was too slow,” she says.

By mid March of 2011, they finished the first iteration of Wantedly. To speed up the development process, Naka decided to learn how to code using Ruby on Rails.

“The thing about building a website is not launching. The crucial part is after launching. You have to keep updating really quickly, keep producing [content and features] very fast in order to actually get active users,” she says.

In June 2011, Wantedly got featured on Techcrunch. With the publicity she was able to gain traction. Facebook’s UX also played a role.

“Back then Facebook did not have a lot of privacy settings. They had a box where it said it will display what you signed up on your profile. Last time, people just kept the checked box on, so [when they signed on Wantedly], it got shared on their wall. They made it viral at a small scale and I was able to acquire 10,000 users within a month,” says Naka.

The traction helped Naka to get more new hires as people were starting to take her product more seriously.

“I was able to hire proper full-time engineers. But my code was bad and messy. So we had to build from scratch but with the same user interface and same database,” she says.

In June 2012, Wantedly officially made its debut in Japan.

Where passion meets work

At the heart of Wantedly’s core ideals is not just to match people with the right jobs; It is about transforming the way people perceive the nature of a salaried job.

“Most people see work as simply work. That’s not what we see work as. We want to change work into a concept where it’s more exciting; We want it to be something you can focus on, one that would allow you to make a social impact,” says Naka.

Naka, who draws inspiration from the principles outlined in Daniel Pink’s Motivation 3.0 book, says that she has applied this philosophy to the operational culture of Wantedly.

“First we give ownership to each member. Even at the junior level, they have autonomy on how they solve the problems or build the products they are going to work on,” she says.

Also Read: Finding the right cultural fit for your next job just got easier

“Second is mastery — we give employees the right set of challenges everyday; Otherwise, they are going to be too bored or too overwhelmed. It’s important for managers to break down the tasks into something that will provide the right challenge even for the junior people.”

“Lastly, purpose is really important. It’s an obligation for companies to state their messages clearly. We communicate these to employees once in a while, and indicate to them clearly the direction we are heading at. We give quantitative figures as well. For example, like by X day, we try to grow X figure.”

Naka emulates the working culture of Facebook, where the engineers and designers are given full autonomy to work on problems.

The company also eats its own dog food. Naka says 70 per cent of the hires at Wantedly come from their own platform.

On new hires, she says she is not particular on their educational qualifications, but having the right attitude and abilities are more important.

“We check their smartness, purpose, commitment and skillsets. We also look at their ability to take advice and feedback, we don’t want them to be stubborn,” she says.

The perils of mis-hiring

Despite Wantedly’s success as an alternative job platform, Naka admitted she made mistakes in the hiring process at first.

“For me, Wantedly was the first time I experienced hiring people. In the beginning, I didn’t believe in interviews because I thought they were all crap — you just deceive yourself in front of interviewers and if you really capable of showing off in a good way you get the job,” she says, with a laugh.

“So I didn’t do interviews. I just hired someone I knew when I was at Facebook — and that was a really bad decision. Interviews are there to set the expectations of both parties. You need to do that or both parties will be unhappy,” she says.

And so there were mis-hires — a costly mistake that was exacerbated by the laws of Japan.

Also Read: ‘Culture fit’ might be more detrimental to your organisation than you think

“In Japan, there is a less liquidity in terms of the labour force. You can’t really fire people in Japan because of regulations. Once you hire, it’s like a permanent hire. Even in a startup, you can’t fire. Letting people go is super hard compared to countries like the US,” she explains.

“So I didn’t know what to do for six months, and the situation got worse and worse. Our plan was to hire a job manager who could get rid of this people, but it took us so long to hire a job manager. What we should have done was to talk to this people. I could have done something but I didn’t,” she says.

Eventually, through a series of conversations and annual reviews, employees left the company. Naka says some had come from large corporations and couldn’t adapt to the startup environment and left because they eventually felt uncomfortable.

“It’s like if you work too long in large enterprise, it becomes your sentence!” she says, with a laugh.

Still, she says hiring people from large corporations would become integral when the company scales.

“If your company is about 200 people, you probably need to start hiring more established people who have worked in large enterprises so that way they can deal with large clients. But when you are at a small stage, you don’t really want to hire people from traditional Japanese companies because they treat work as a 9 to 5 job,” she explains.

Naka has, however, come to embrace the whole episode as part of a painful but much-needed learning experience — a rite of passage that every young company must go through.

“I lost a lot of precious time worrying about the situation when I could have worked on product and marketing, but I think this is a pitfall for most companies. We hear the history of many great companies experiencing the same problem,” she says.

Getting investor attention

Due to a healthy revenue stream, Naka says Wantedly was able to bootstrap in the beginning. But it soon received the attention of investors, hungry for an up and coming tech investment.

“In Japan, there are [fewer] entrepreneurs than money available. Investors are eager to look for a new company to invest in. For us it wasn’t that hard because we were featured on cool media [TechCrunch]. But if you don’t really have a cool product, it would be hard,” says Naka.

Wantedly was first funded by serial entrepreneur Shinji Kimura, the co-founder of news curation app Gunosy and payments platform AnyPay. Then it received money from CyberAgents, and a year after, it raised funding from the Nikkei newspaper.

Naka did not disclose the investment amount.

“When I look back, I felt that I didn’t have to raise that much money but then I had no clue. I just thought because other people are raising money like crazy, so I had to as well,” she says.

Present day

Today, Wantedly has morphed into a platform that is available across 15 countries, logs over 1.5 million visitors monthly. It has over 20,000 clients including startups such as Uber and Airbnb, as well as corporations including Sony and Panasonic.

Since its inception, it has launched three new features: Wantedly Visit, where prospective interviewees can visit the companies they wish to work at, and get to know the profiles of their employees; Wantedly Chat, a team chat app that works like Slack; and Wantedly People, an AI-based business card reading app that can analyse up to 10 business cards at once.

Just last week, Naka flew down to Singapore to open its new office. Amidst the glitz and glamour of the launch pumping with hard-pounding electronic music, Naka stood by the sound booth, decked in a plain outfit of a black shirt and slacks, silently observing the young and effervescent crowd — the generation who would lead the charge in the new innovation-driven economy.

Then a person approaches her, and she lights up, ever ready to be the face of Wantedly, ever ready to receive a new convert.

—-

Image Credit: Wantedly

The post Wantedly’s Akiko Naka: On breaking ranks with traditional Japan and finding her true north appeared first on e27.