The boss of Vertex Ventures believes that startups and investors need to identify future problems early — before they sign the deal

In the growing sea of VCs entering the burgeoning Southeast Asian tech landscape, Vertex Venture Holdings, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Singapore government’s Temasek Holdings, is an old but familiar and stalwart supporter of startups.

Founded in 1988, the investment firm has made several early-stage deals in what are some of today’s most prominent tech companies, across Asia and the US. These include GPS company Waze, ride-hailing giant Grab, social entertainment and dating platform Paktor, and more.

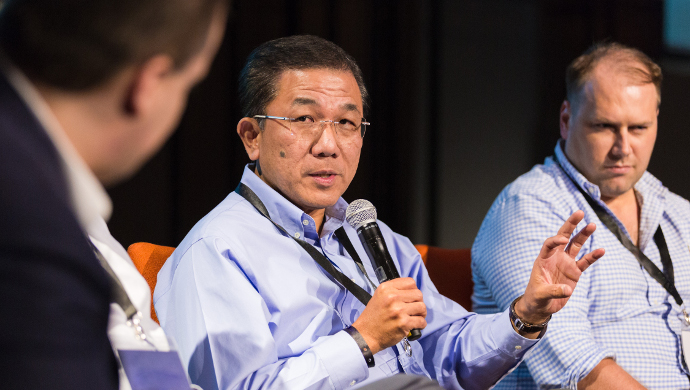

Leading the hunting party to scour for deals is Chua Kee Lock, Vertex’s Group President and CEO. He previously co-founded and led Mediaring — a Singapore-based Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) company — from 1997 to 2000. Afterwards, he joined Biosensors International from 2006 to 2008, as President and Executive Director.

e27 met up with Chua at Vertex’s office high up in the Raffles City Tower to pick his brains on entrepreneurship and the state of the ecosystem today.

Here are the edited excerpts:

On how he vets and helps startups and entrepreneurs

The key is whatever industry or business startups are in, we ask ourselves: Is this transformational? Is this going to make a difference?

If it is going to make a lot of difference over a period of time then you should try to get involved, right? Then the next thing concerns the entrepreneur — is the entrepreneur good enough? If the entrepreneur good enough, then you should try to support them, right? Those are the two fundamental principles.

If the entrepreneur is good and if they execute the plan well and build a good team around them, they would get to where they would need to be.

Every company we invest in, we sit on the board and we help them do some basic things. For the case of Grab, we introduced them to the necessary people, to open doors for them.

When they were trying to recruit people, we helped them recruit certain key people. We provide operational support, but we don’t run the business; the companies run their business.

On whether he looks at past examples during the vetting process

When you look at GrabTaxi (now known as Grab), there were no previous examples to draw upon. Sure, there was Uber, but Uber’s model was different: they provided a limousine service; GrabTaxi was about providing connectivity to taxis. Now their services are similar, but when they first started, their value points were quite different.

In Southeast Asia, you have to remember one thing, 40 years ago in Singapore, private-hire cars used to be common, people just flagged them down — anyone could be a private-hire driver; then the government made them illegal — in part, because of accidents — and made taxis a regulated industry.

So now suddenly, when you have a mobile app (for taxis), you have to ask: Is this legal? Is it operating in a legal grey area? We had to be convinced that GrabTaxi was good for the industry. We made the right call — but we could have been wrong.

On whether he is worried about investees not turning a profit

No, if the company is making progress, you can always raise the next round. If the company cannot do well, then it won’t raise the next round, then it cannot grow and will just stop.

Ultimately, companies have to grow big enough to sell or go public (IPO). Short-term losses is not an important thing to focus on. If the model works, you don’t have to worry.

[At this point I mentioned how RedMart was struggling before it got acquired.]

Regarding RedMart, if people really know the history of this model, in 1997, there was a similar company called Webvan. Sequoia put in US$30 millioninto the company. Webvan’s idea was to deliver grocery to everybody using tech.

But for every delivery they shipped out, they lost about US$2. So that means the more they sold, the more money they lost [Webvan eventually folded]. So no matter how you scale, it won’t work — it has nothing to do with whether the business was too early or too late.

If the more you scale the more you money lose, it won’t work; if the model works, it’s only a matter of time before you make a profit. Short-term costs such as marketing can be overcome.

On why he invested in grocery startup HappyFresh despite RedMart’s dismal prospects

Not all grocery delivery startups have the same business model. RedMart is an inventory model business, it is very hard to sustain because you are fighting with the traditional groceries.

First of all, the grocery business model is a low margin business (15 – 20 per cent gross margin). It’s a business of scale. So you are competing with supermarkets on the basis of volume — and that is why RedMart’s model is hard to scale.

Companies like HappyFresh and InstaCart have a different model. Their model is not to compete against groceries but to be complementary. They help supermarkets increase their revenue for a small fee, by becoming a partner. For example, they may be able to deliver 10 per cent more revenue to the supermarkets in exchange for 10 per cent of the profit, so there’s no issue.

You must remember: delivering groceries is also convenient, and that may lead to more frequent purchases.

On how he trains his business partners to adapt to different industries and models

This is the hardest part of the business, you have to relearn and learn at the same time. For example, in an industry like e-commerce, its characteristics could evolve and become different over time.

We have to continually ask ourselves: Is our strategy still working?. Has the market changed? Has the tech changed? Has the core of the basic business model changed?

Then we have to pinpoint which aspect of the business has changed.

That’s why in this business, a lot of the very good VC, they learn and relearn; the bad ones, they do well one time but apply the same formula across the board, so when the market has shifted away and they apply the same formula, they may not succeed.

You have to be conscious of the need to learn and relearn.

On the later-stage funding gap in Southeast Asia and pivoting

I say the later-stage funding gap is a problem in any ecosystem, initially. Over time, it will all be solved. There is less of it in China and the US. In Southeast Asia today, most people are concentrated in early-stage rounds.

Half of the companies that receive early-stage (Series A) funding will make it to the next round. It is the natural rule of the ecosystem.

Getting Series A funding is like chasing a dream. At this stage, the startup is in the dream/concept phase. Entrepreneurs at this stage dream big, and when people are in the ‘dream’ mode, they usually just think about the upside and not the downside.

It’s like the period of courtship: you fall in love and only think about lovey-dovey, positive things. But once you are married and the honeymoon is over, you have the responsibility of family, in-laws, kids; you have to deal with sickness and a lot of problems happen, and then you say life sucks.

It goes the same with startups: entrepreneurs only think about the downsides during the later stages.

The reality is that not all startups can execute well. Not all tech or market issues can be solved and not all funding can be raised successfully.

If you are a more experienced investor, you will recognise these things. Once the money is in, you will quickly work with the founder to solve this. Before marriage both parties will talk about it, being aware that one day, such problems will arise.

Nobody in the Series A stage will want to talk about problems first; but we at Vertex are different, we will talk through potential problems with the entrepreneurs. Some of them find it unusual because we are not even partners yet. It’s like talking about marriage problems during courtship. We talk about whether the money they are asking for is enough, whether their business model is right, whether they need to pivot, etc.

Also Read: 3 important entrepreneurship lessons I learned from the FBI

For one of the companies we invested. I asked the founder: “Are you sure this is the beginning or this is the end?” — this is after we put the money in. He said: “What kind of question is this?”

Basically, I was asking whether his product was already finished or the beginning of something bigger. I told him that I thought there could be more to it but he needed to figure it out.

Eventually, he went back and figured it out. He pivoted, and we went along with the pivot.

On the lack of tech IPOs on the Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX)

I think this issue has gone on for too long. For the sake of the argument let’s use an analogy.

You have injured your toe, you didn’t go see a doctor and then you injure your next toe, then you say: “Ok, I still got three more toes to go.” But by the time you get to the fourth toe, you say “Shit! I have to amputate all of them now.”

So now that you have amputated four you cannot walk — and that is the case with the SGX.

SGX has been successful as a real estate investment trust, and they have gone on (relying on that model) for too long. Because of that, many of their investors are from that sector.

Real estate investment trust investors are not bad people. Their formula is simple: “I give you x amount of dollars, you give me 3 per cent return a year. Don’t lose my money and that is good enough.”

Tech stock investors are different, they say: ” if I bet correctly, I can increase my investment returns by 10 to 15 per cent per year. Sometime I will lose and that is ok. On some stocks I may make 25 percent and some I make zero.”

So in a market that is all about encouraging yields, naturally, the valuation would come down. For example, if real estate grows 3 per cent a year, the valuation will be pegged to a 3 per cent basis.

Also Read: SGX partners A*STAR to help startups access capital markets, accelerate technological growth

But tech stocks are different. They are based on futures. For example, if I perform this way next year I will triple the number. And because I triple, you must give a valuation of 1.5 times of what I am now because that’s fair.

Now SGX has woken up and wants to attract tech companies to list. But its market is based on yield and not future earnings/or profit.

The first step is to find the right investors to move here. If a tech company comes here, it will not get the valuation it needs, because the multiple is based on 3 per cent growth per year — a very low number, so it will never come here.

—

Image Credit: Vertex Venture Holdings.

The post We like to address marriage problems during courtship: Vertex Ventures CEO Chua Kee Lock appeared first on e27.